Pitch-Fork Bifurcations

This will be a very brief treatment of bifurcations of the pitch-fork variety. This will conclude our study of bifurcations for the time being.

Pitchfork bifurcations are common in physical problems that involve symmetry. An example of such a system would be a beam with a weight placed on top of it. As weight is added on top of the beam, the beam holds the mass without any trouble. At some critical weight, the beam begins to buckle and this may happen in either direction. This buckling is an example of a pitchfork bifurcation. There are two types of pitchfork bifurcations: supercritical and subcritical. We will start with the easier of the two: supercritical.

Supercritical Pitchfork Bifurcation

The normal form of the supercritical pitchfork bifurcation is

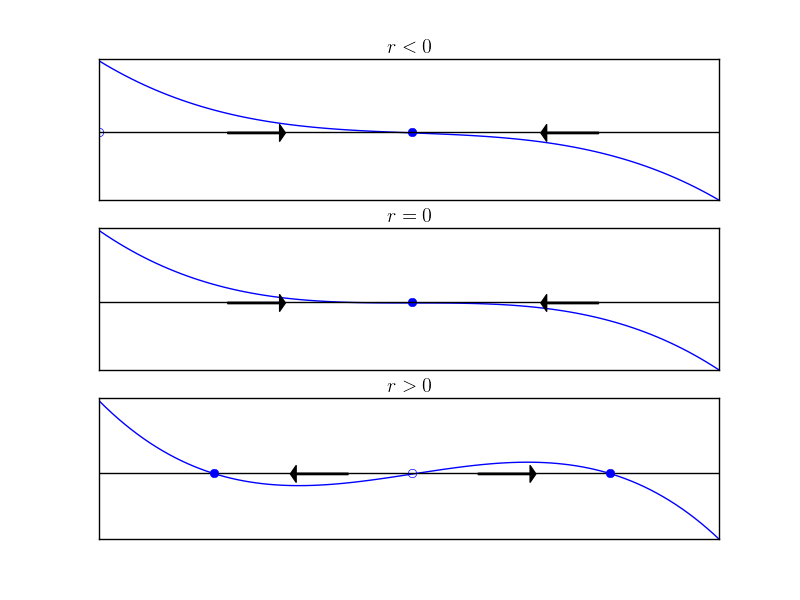

\[\dot{x} = rx - x^3\]Here is the vector field for various values of $r$.

When $r$ is negative, $f$ has one stable fixed point at $x^* = 0$. As we increase $r$, this fix point remains stable however it is much “less” stable in the sense that we have lost the exponential term that was driving the solutions to stability. This is known as critical slowing down in the physics literature. When $r > 0$, $x^* =0$ now becomes an unstable fixed point and two new fixed points emerge symmetric about the origin at $x^* = \pm \sqrt{r}$.

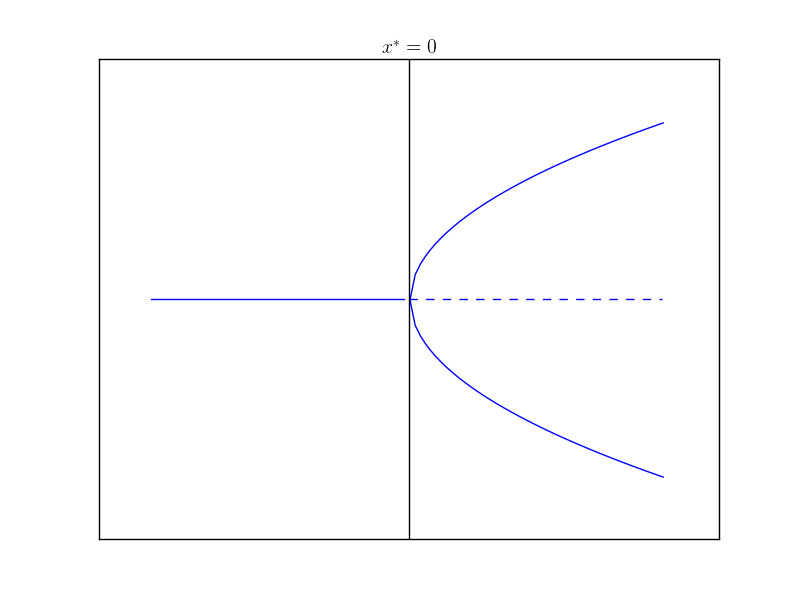

The bifurcation diagram makes it clear where the name ‘pitchfork’ comes from

Subcritical Pitchfork Bifurcation

The normal form of the subcritical pitchfork bifurcation is

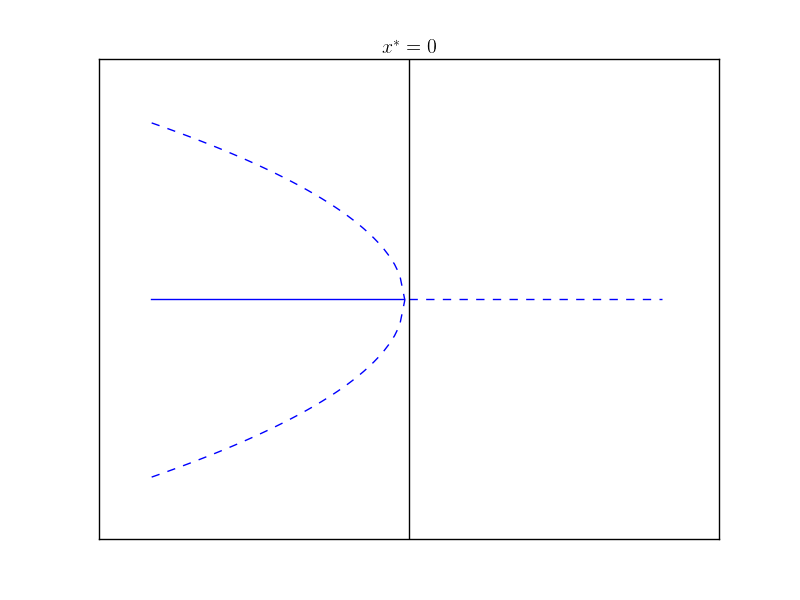

\[\dot{x} = rx + x^3\]Compared to the supercritical case, where the cubic term was stabilizing, that is bringing the terms closer to $x=0$ now it is destabilizing, i.e. driving solutions away from $x=0$. Next is the bifurcation diagram for the subcritical case.

Now there are no non-zero stable points. In fact, the destabilizing effect of the cubic term causes the solutions $x(t) \to \pm \infty$ for any non-zero initial condition $x_0$.

In real physical systems, this explosive tendency is countered by higher order terms that pull the solutions back. Since we still want to model the symmetry inherent to the problem the next term that can provide such stability must be fifth order

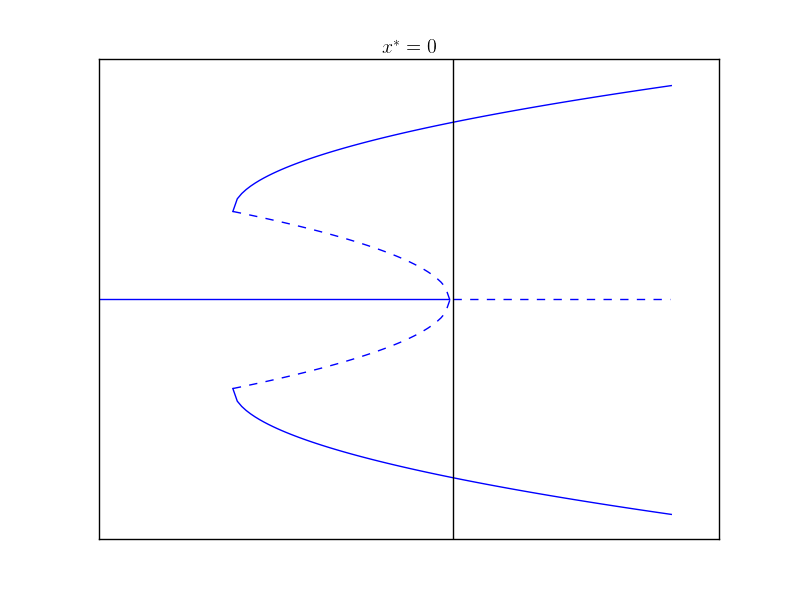

\[\dot{x} = rx + x^3 - x^5\]Now the bifurcation diagram looks like this:

Notice the overlap of the stable portions of the plot. Indeed, now which branch the solution ends up on depends on which branch it started on. This can also lead to jumps or hysteresis where solutions jump from one stable branch to another.

This was just a short post to highlight a few facts about pitchfork bifurcations and to bring the study of bifurcation theory on this blog to a close for the time being.