Weak vs Strong Extrema in The Calculus of Variations

In the Calculus of Variations, extrema are put into classes “strong” and “weak”. I was a little confused when I first read about these. When I saw this question on Mathematics Exchange, I figured there may be others who could benefit from the simple picture I keep in my mind’s eye for understanding why these extrema are named thus.

First a few definitions are in order. By a linear space, $V$ over a field of scalars, $F$ we mean one that possesses the following attributes. For any $f,g, h \in V$ and $\alpha, \beta \in F$,

- $f+g = g+f$

- $(f+g)+h = f + (g+h)$

- There exists and element $0 \in F$ such that $f + 0 = f$ for any $f \in V$.

- For any $f \in V$ there exists $-f \in V$ and $f + (-f) = 0$

- $1\cdot f = f$

- $\alpha(\beta f) = (\alpha \beta) f$

- $(\alpha + \beta)f = \alpha f + \beta f$

- $\alpha(f+g) = \alpha f + \alpha g$

We refer to a function, $|\cdot| : V \to \mathbb{R}$ as a norm on $V$ if it satisfies the following criteria:

- $|f| \ge 0$ and $|f| = 0 \iff f =0$

- $|\alpha f| = |\alpha | |f|$

- $|f+g| \le |f| + |g| $

We call the space a normed linear space if, $V$ is a linear space that is also equipped with a norm.

Now we define a few normed linear spaces of functions that will be the main point of this post.

The function space $\mathscr{C}(a,b)$ consists of those functions, $y(x)$ that are continuous on the closed interval $[a,b]$. The norm of $\mathscr{C}(a,b)$, denoted $|\cdot|_0$ is defined as

\[\|y(x)\|_0 = \max_{a \le x \le b}\|y(x)\|\]By $\mathscr{D}_1(a,b)$, we mean those functions $y(x)$ that are continuous, and have continuous first derivative. The norm of $\mathscr{D}_1$ is

\[\|y(x)\|_1 = \max_{a \le x \le b}\|y(x)\| + \max_{a \le x \le b}\|y'(x)\|\]It is clear that if a function, $y$ belongs to $\mathscr{D}_1$ then $y \in \mathscr{C}$. This is because, for the function to have a derivative at all points in the interval it must also be continuous on $[a,b]$.

With these, and the definition of a functional we are ready to state the last two definitions and hit the main point of this post. For these definitions, we consider functions that are defined on the interval $I=[a,b]$.

A functional, $J[y]$ is said to have a weak extremum for $y=\hat{y}$ if there exists $\epsilon \gt 0$ such that $J[y] - J[\hat{y}]$ has the same sign for all $y$ in the set $\{ y : |y(x) - \hat{y}(x)|_1 \lt \epsilon; x \in I \} $ where $|\cdot |_1$ is the norm in $\mathscr{D}_1$.

We say that a functional, $J[y]$ has a strong extremum for $y=\hat{y}$ if there exists $\epsilon \gt 0$ such that $J[y] - J[\hat{y}]$ has the same sign for all $y$ in the set $\{ y : |y(x) - \hat{y}(x)|_0 \lt \epsilon; x \in I \}$ where $| \cdot |_0$ is the norm in $\mathscr{C}$.

The confusion for me came in with the naming convention. Why is the one called weak and the other strong? Furthermore, why is my book stating it is so obvious that a strong extremum is automatically a weak extremum? My confusion arose from the fact that if $y \in \mathscr{D}_1 \implies y \in \mathscr{C}$, so I incorrectly reasoned that since a weak extremum is related to the norm in $\mathscr{D}_1$ and a strong extremum to that in $\mathscr{C}$ that the naming convention (and thus the implication) should be the other way.

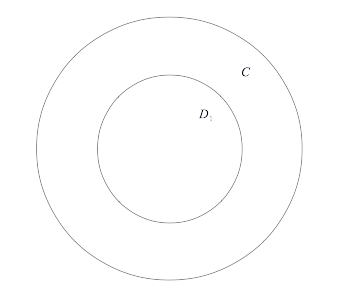

The error in this line of reasoning was corrected for me by a simple picture:

As we stated earlier, if a function is in $\mathscr{D}_1$ it is automatically in $\mathscr{C}$. So $\mathscr{C}$ is the “bigger” class of functions. Thus, if $\hat{y}$ is a relative maximum of the functional, $J$ within the bigger class of functions (a strong extremum), it will automatically be a maximum within the class of functions that is contained within it (namely, $\mathscr{D}_1$), i.e. a weak extremum. However, if it is just a maximum within the smaller circle, that does not mean there isn’t a function that may achieve a more extreme value of $J$ within the larger class of functions.