Some Geometry of Analytic Functions

We will now look at a couple of results pertaining to the geometry of analytic functions. We will conclude the post with a proof of the maximum modulus principle and briefly discuss areas of application.

Before we begin, we state one result that we will not prove.

Proposition

If $f$ is an analytic function on a domain $D$ and

\[f^{(k)}\left(z_0\right) = 0 \qquad k=0,1,2\ldots\]for some $z_0 \in D$. Then $f(z)=0$ for all $z \in D$.

This result can be reached by looking at the power series representation of $f$:

\[f(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n\left(z-z_0\right)^n \qquad a_n=\frac{f^{(n)}(z_0)}{n!}\]and also depends on properties of the real and complex numbers.

Now, the first result we will prove is a statement about the zeros of an analytic function.

Proposition

If $f$ is an analytic function on a domain $D$ and \(\left\{z_n \right\}\) is a sequence of zeros of $f$ that converge to some $z_0 \in D$, then $f$ is identically zero. That is, the zeros of an analytic function are isolated.

Proof

Throughout, we will make use of a couple of statements in this post. Since $f$ is analytic, it has a power series valid on some disc $\left|z-z_0\right|\lt\delta$, for some $\delta \gt 0$.

\[f(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n\left(z-z_0\right)^n\]Since $f$ is continuous and \(\left\{z_n\right\} \rightarrow z_0\) as $n \rightarrow \infty$, we know that $f\left(z_0\right)=0$ as well.

In what follows, we will assume that $a_0, a_1,\ldots, a_{N-1}$ are zero and will show that $a_N$ is also zero. (See the proposition near the end of this post for why we assume this.)

Define $g$ as

\[g(z) = \begin{cases} \frac{f(z)}{\left(z-z_0\right)^N} & z\ne z_0\\ a_N & z=z_0 \end{cases}\]From the earlier post, we know that $g$ is analytic. Also note that,

\[g\left(z_n\right) = \frac{f\left(z_n\right)}{\left(z_n-z_0\right)^N} = 0 \qquad n=0,1,2,\ldots , \; z_n\ne z_0\]Then

\[a_N = g\left(z_0\right) = \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} g\left(z_n\right) = 0\]So, all the terms of the power series of $f$ are zero.

Then, by the definition of the terms of the series we know that

\[f^{(n)}\left(z_0\right) = 0 \qquad n=0,1,2\ldots\]So $f(z)=0$ for all $z \in D$. $\Box$

Next, we see that we can say quite a bit about the range of a non-constant analytic function.

Theorem

Let $f$ be a non-constant, analytic function on a domain $D$. Then the range of $f$ is an open set.

Proof

Let $z_0 \in D$ and write $f\left(z_0\right) = w_0$. Since $f$ is not constant $f-w_0$ is not identically zero so it has a zero of order $m \ge 1$.

Let $r \gt 0$ be such that \(f\left(z_0\right) - w_0\) does not have any zeros inside the punctured disc \(0 \lt \left\|z-z_0\right\| \le r\).(This is possible because the zeros of an analytic function are isolated.) Let $\delta$ be the minimum value of \(\left\|f\left(z_0\right) - w_0\right\|\) on \(\left\|z-z_0\right\| \le r\) and $w$ be any point such that \(\left\|w - w_0\right\|\lt \delta\). Then,

\[\left|\left(f(z) - w\right) - \left(f\left(z\right) - w_0\right)\right| = \left|w - w_0\right| \lt \delta \le \left|f(z) -w0\right|\]So by Rouché’s Theorem, $f(z) - w$ and $f\left(z\right) - w_0$ have an equal number of zeros inside \(\left\|z-z_0\right\| = r\) . But we know that $f\left(z\right) - w_0$ has exactly $m$ such zeros. Therefore $f(z) - w$ also has $m$ zeros. So $w$ lies in the range of $f$. This shows that every point in the range of $f$ is at the center of a disc of values also in the range of $f$ and we have proved the theorem.$\Box$

An important corollary to this theorem is the Maximum Modulus Principle.

Maximum Modulus Principle

If $f$ is analytic on a domain $D$, then \(\left\|f\right\|\) does not attain any local maximum on $D$.

Proof

If $\left|f\left(z_0\right)\right| \ge \left|f\left(z\right)\right|$ for all $z \in \left|z-z_0\right| \lt r$, $r\gt0$ then $f\left(z_0\right)$ must be on the boundary of the set \(W=\left\{f\left(z\right) : z \in \left\|z-z_0\right\| \lt r \right\}\) but this contradicts the fact that $W$ is an open set.$\Box$

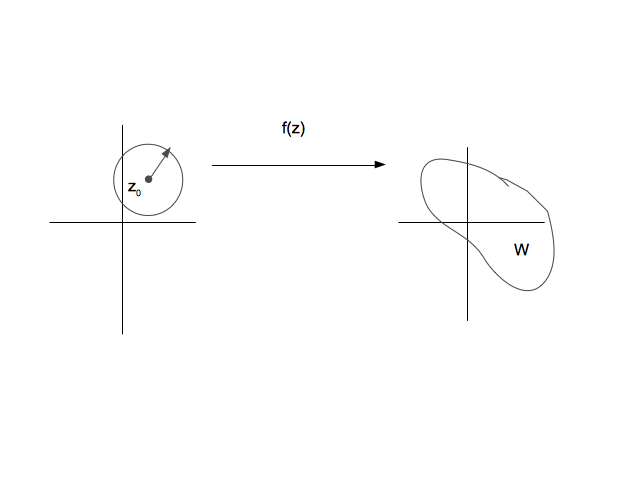

The first line in this proof took me some time to feel comfortable with. Now it seems obvious, but it was the following picture that I had in my mind that convinced me.

The complex, analytic function $f$ maps the circle on the left to the set on the right. The point with the maximum modulus is obviously the point farthest from the origin in the right plot. This clearly must be on the boundary of $W$.

Example

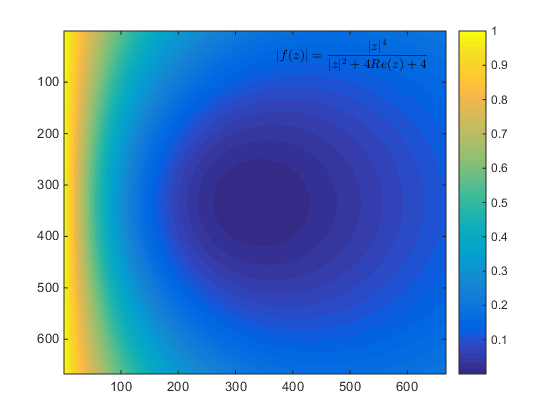

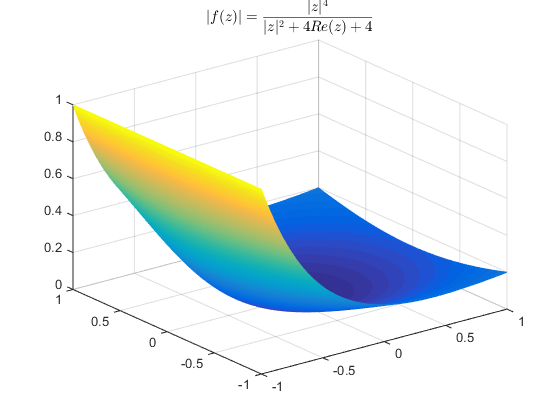

By the maximum modulus principle, we know that the maximum value of the modulus of $f$ given by,

\[f(z) = \frac{z^2}{z+2}\]on $\left|z\right| \le 1$, cannot come inside $\left|z\right| \lt 1$. So it must come on the boundary $\left|z\right| = 1$. Indeed, the modulus of the function $f$ above is

\[|f(z)| = \frac{|z|^4}{|z|^2 + 4\text{Re}(z) + 4}\]from which it is clear that the maximum on the disc $\left|z\right| \le 1$ comes when $\left|z\right| = 1$ and $\text{Re}(z) = 0$.

An application of the maximum modulus principle tells us that if we have a constant, sourceless ($\int_{\gamma}f\cdot n\,ds=0$ or all smooth, simple, closed curves $\gamma$ in $D$), irrotational flow on a domain $D$, then at no point in $D$ is the speed of the fluid the greatest.